Whistleblower Protection in the EU, Switzerland & Beyond

This article aims to provide a high-level overview of the protection of whistleblowers in the European Union (EU) and Switzerland, whilst highlighting one stark contrast between the two. It also addresses the question surrounding the extraterritorial reach of the EU Whistleblowing Directive and its ramifications beyond the EU borders.

1) Whistleblower Protection in the European Union

The

European Union (EU) Directive 2019/1937 on the protection of persons who report breaches of Union law – commonly referred to as the EU Whistleblowing Directive – was adopted on 23 October 2019 and came into effect on 16 December 2019. Member States had until 17 December 2021 to transpose it into their national legal framework, even though the vast majority of Member States completed their implementation process past that deadline, with some as recently as a few months ago (including Spain, Italy, Germany, and Luxembourg).

The EU Whistleblowing Directive stemmed from the necessity to harmonize and enhance the enforcement of Union law in important policy areas where breaches of EU law would likely cause harm to the public interest, such as financial services, environmental protection, public procurement, and nuclear safety. In order to achieve that goal, the Directive created a comprehensive legal framework to be applied across all 27 Member States for the protection of whistleblowers who report such breaches and safeguard the interests of the Union.

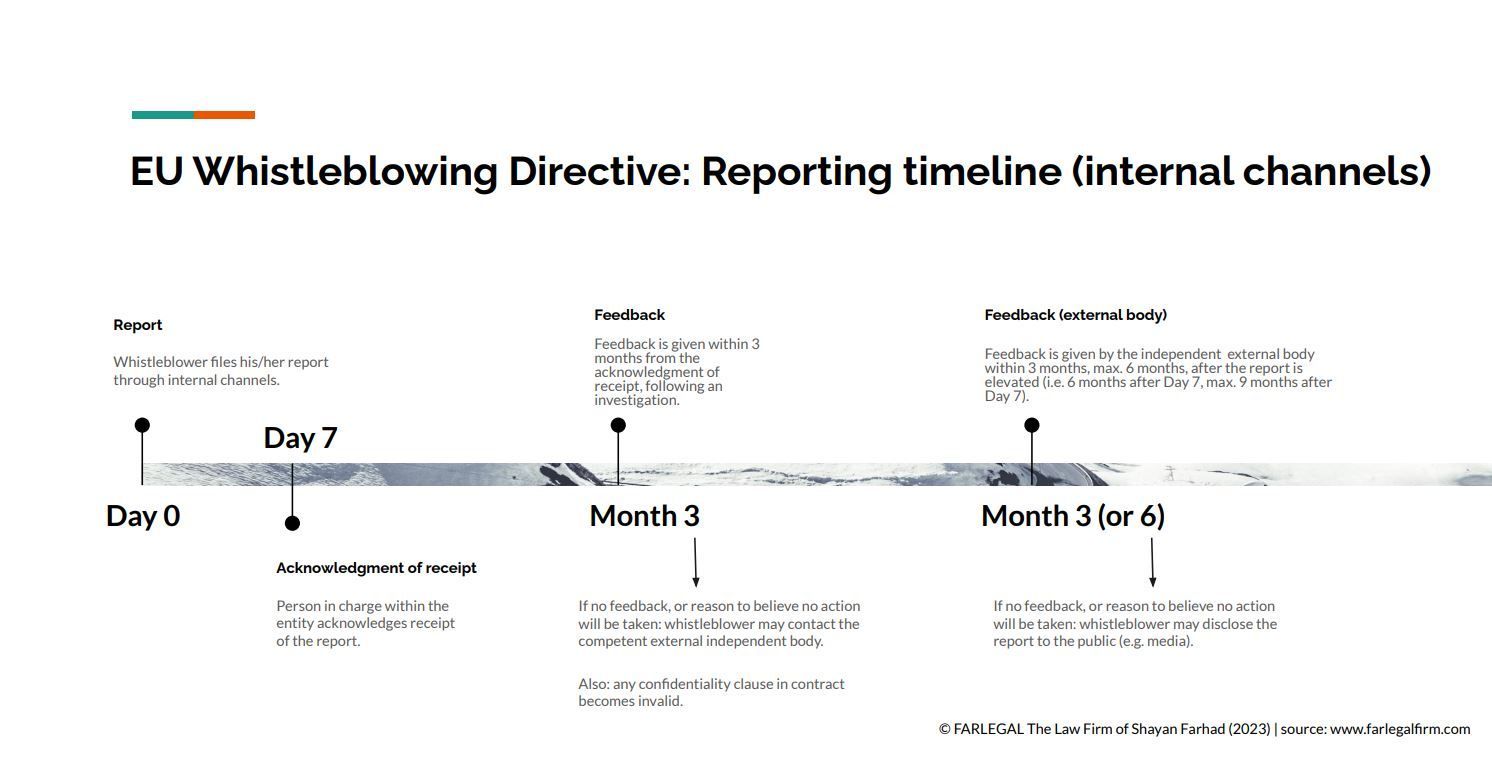

Essentially, the Directive lays down common minimum standards that all 27 Member States must observe and integrate into their respective national laws in order to ensure adequate whistleblower protection. In a nutshell, Member States are legally required to implement and provide whistleblowers with effective and confidential reporting channels (both internally and externally), observe very strict harmonized timeframes for dealing with whistleblowing reports (see chart below), and establish a robust anti-retaliation system for whistleblowers. As per the Directive, Member States are also required to provide the same level of protection to whistleblowers who report breaches through public channels (e.g. the media) in compliance with the rules.

As with any directive, Member States are free – and even encouraged – to go beyond the common minimum standards and provide greater protection. In the case of the EU Whistleblowing Directive, most Members States have indeed widened the scope of protection offered to whistleblowers or opted in on certain areas that the Directive left to their discretion (such as anonymity, i.e. the right for whistleblowers to report breaches anonymously). While all national laws will reflect the Directive’s core minimum standards, this does mean that legal variations exist across the EU and, as such, the exact scope of protection and requirements varies from Member State to Member State.

Here’s a look at two of the key standards: who and what is covered by the Directive.

- Who qualifies as a whistleblower under the EU Whistleblowing Directive?

Under the EU Directive, a whistleblower is any person in the private or public sector who acquires information on breaches “in a work-related context” (Article 4).

The scope is therefore extremely broad as it applies regardless of the person’s employment status (employed, self-employed, volunteer, paid, unpaid, etc.) or citizenship (EU or non-EU citizen), and even regardless of whether the employment has begun or ended.

It also applies to third parties to the whistleblower, namely persons who are connected to the whistleblower and who could be subject to retaliation as well (such as colleagues or relatives).

- What are the breaches the EU Whistleblowing Directive covers?

Whistleblowers are protected insofar as they report information on breaches stipulated in the EU Whistleblowing Directive, respectively in the relevant national law implementing it.

There are ten categories of wrongdoing that explicitly fall within the scope of the Directive (Article 2). They include public procurement, financial services, protection of the environment, public health, protection of privacy and personal data.

As per the Directive, most Member States have widened the material scope by adding further categories of breaches into their respective national laws. Some have introduced the notion of “public interest”, which gives leeway to authorities as it allows a case-by-case analysis regardless of whether the whistleblower reports an express breach (such as France, The Netherlands, Italy). Denmark has gone as far as to include discrimination, violence and harassment as categories of wrongdoings covered by its whistleblower protection legislation.

2) The Extraterritorial Reach of the EU Whistleblowing Directive

Perhaps the most often left-out yet critical point is the territorial scope of the EU Whistleblowing Directive. This point is particularly relevant given the increasing international presence of companies and organizations, spanning multiple countries and even continents.

In other words: to what extent (if at all) does the EU Whistleblowing Directive apply beyond the EU borders?

This question involves complex sub-considerations, such as the distinction between EU-headquartered entities operating outside of the EU and non-EU entities operating inside the EU. While the answer(s) will partly depend on how the laws implementing the EU Whistleblowing Directive will be applied in the months and years to come, the Directive offers a clue.

In its Recital, the EU Whistleblowing Directive explicitly suggests that internal reporting procedures be extended to reports made within the wider structure of the (UE-registered) entity, not solely within the entity itself (see

§ 55 of the Recital).

Broken down, this means reports made by:

(i) the workers of the entity;

(ii) the workers of the entity’s subsidiaries or affiliates (together with (i): the “group”);

(iii) any of the group’s agents and suppliers (“to any extent possible”); and

(iv) any persons who acquire information through their work-related activities with the entity and the group.

Based on this, it is safe to conclude that the reach of the EU Whistleblowing Directive is aimed to extend beyond the strict borders of the EU. That said, and as evidenced by the language used, it is important to note that some discretion is left to the Member States.

For now, two interpretations can be drawn:

- EU-registered entities that conduct their operations outside the EU through affiliates, subsidiaries, agents or suppliers will likely be bound by the Directive’s requirements even when the suspected breach may have taken place outside the EU.

- non-EU entities that either have a subsidiary or affiliate in the EU or conduct operations within the EU through an agent or a supplier, are strongly advised to examine the specific legal requirements of the EU market(s) they operate in so as to determine whether they fall within the scope of the Directive and act accordingly by implementing the necessary internal regulations.

In any case, all EU-registered entities with 50 and more employees have until 17 December 2023 to comply with the Directive’s requirements, while those in the financial industry must comply with the Directive regardless of that number.

3) Whistleblower Protection in Switzerland

In Switzerland, whistleblower protection in the private sector is lacking. Attempts to implement a national law that would provide protection for whistleblowers in Switzerland have been systematically squashed by the Swiss parliament (as recently as in 2020). There is thus little to no hope that Switzerland will align with European and international standards in the short to medium term.

That said, the EU Whistleblowing Directive is not completely irrelevant to Swiss-registered entities. As seen above, the Directive may still apply in some cases and its relevance is especially true for those Swiss entities that have EU subsidiaries and/or conduct operations within the EU. Swiss entities with a European or international presence should therefore examine whether they fall under the EU Whistleblowing Directive and act accordingly by ensuring their internal regulations satisfy the Directive’s requirements. Swiss entities may choose to do so anyway for other reasons such as preventing potential whistleblowers from going public with grievances that could be dealt with internally, preserving their reputation and image, or cultivating a corporate ethical culture.

Regardless of the above, it is essential to highlight one stark contrast between the EU and the Swiss legal regimes: whistleblowers in Switzerland are not only unprotected, but they also run the risk of facing various forms of retaliation, legal proceedings, and even criminal prosecution. That is particularly the case in the banking sector and includes journalists as well. This is why it is important to use caution and retain legal counsel before undertaking any action.

In fact, Swiss authorities often choose to allocate their resources to prosecute the whistleblowers who report information on wrongdoing, instead of investigating the actual wrongdoing.

Among multiple examples, the most recent one is the "Suisse Secrets" leak of bank client data in 2022 which essentially exposed the hidden wealth in Switzerland of individuals allegedly involved in serious crimes ranging from money laundering to corruption to human trafficking. Earlier this year, the Office of the Attorney General stated that it had opened a criminal investigation into the leak on suspicions of breaches of economic intelligence, trade secrets, and banking secrecy laws.

Most alarmingly, journalists in Switzerland also face criminal prosecution for reporting and publishing information they receive from whistleblowers in the banking sector. That is due to Article 47 of the Swiss Federal Banking Act, which punishes anyone who discloses banking secrecy information or profits from such information. But it impacts journalists and the freedom of the press, too: under that legal provision, journalists who expose wrongdoing in connection with suspected white-collar crimes (such as money laundering or tax evasion), or any information of public interest arising from leaked banking data, all face criminal prosecution. Calls for reform have been left unanswered so far.

***

How FARLEGAL can assist

FARLEGAL has experience in navigating the complexities and intricacies of whistleblower protection on an EU and international level, and has expertise in litigation and federal criminal prosecution. The firm is committed to helping those who safeguard the public interest by standing up for what is right and speaking out against misconduct and wrongdoing. This also includes journalists who fulfill their duty to the truth by exposing facts. Regardless of where they are based and what their specific needs are, FARLEGAL assists and provides legal support to whistleblowers and those who report information in the public interest.

The firm also has experience in assisting entities looking to comply with the EU Whistleblowing Directive and develop internal whistleblowing regulations in line with both the EU Directive and the relevant national law(s).

Contact us if you are in need of immediate assistance or to discuss ways in which FARLEGAL can help you.